- Clinical insight

- Reading Time: 7 Minutes

Stress and memory – the physiology

There is much evidence to show that stress affects multiple facets of mood, sense of well-being, and health, but could it also affect memory and learning?

Stress is ubiquitous in our modern lives, and work-related stress, in particular, is a growing health problem. There is much evidence to show that stress affects multiple facets of mood, sense of well-being, and health, but could it also affect memory and learning?

An abundance of research has been undertaken in recent years demonstrating the negative effects of stress and anxiety on human memory and learning. But to understand how stress affects memory we need to review the effects of stress on the body, and how a memory is made.

Stress & its effects on the body

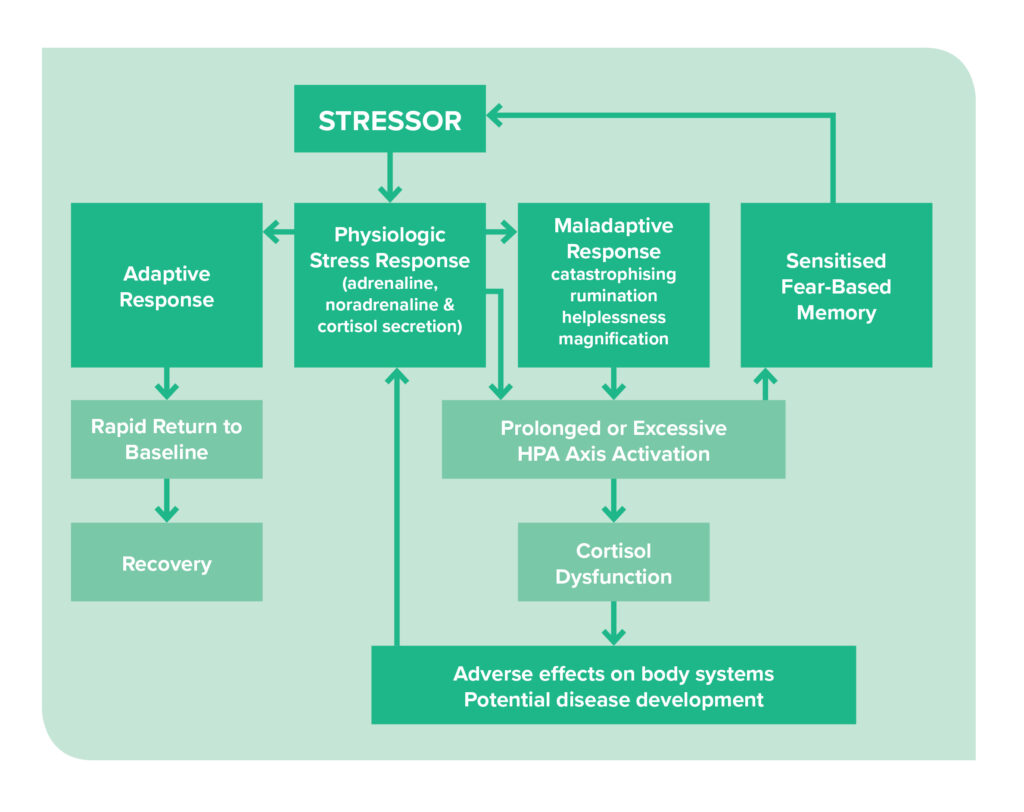

When the human body is exposed to a stressor, either internal or external, it sets off a cascade of reactions known as the ‘stress response’. Stress can have a wide variety of effects on the body ranging from alterations in homeostasis to life-threatening effects.1

In response to acute stress, the amygdala (found in the brain’s limbic system) rapidly activates responses from both the autonomic nervous and neuroendocrine systems in an attempt to return the body to homoeostasis.2

The release of catecholamines, including adrenaline and noradrenaline from both the adrenal medulla and the locus coeruleus in the brain, prepare the body for ‘fight-or-flight’ responses. Once released into the bloodstream these neurotransmitters alter several physiological functions, such as cardiovascular capacity, metabolic resource allocation and immune activation, to effectively respond to the threat.2-4

At the same time, the amygdala activates the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis by signalling the hypothalamus to release corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), which triggers the release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). ACTH, in turn, causes the adrenal cortex to produce and release cortisol into the bloodstream. Cortisol reaches peak level concentrations approximately 20 to 30 minutes after the onset of the initial stress and can remain elevated for several hours. Cognition and behaviour may be affected with this readily available supply of cortisol to the brain.2,3

Diagram adapted from: Hannibal KE, Bishop MD. Chronic stress, cortisol dysfunction, and pain: a psychoneuroendocrine rationale for stress management in pain rehabilitation. Phys Ther. 2014;94:1816–825.

Normally, the stress response will rapidly return the body to homoeostasis through negative feedback mechanisms; however, with chronic stress (prolonged and/or intense stress exposure) the HPA response is more complex. It can lead to reductions in cortisol release, glucocorticoid insensitivity, and alterations in cortisol rhythms, which can contribute to disease pathogenesis.4,5

Want a closer look at the interplay between stress and memory formation? Read our latest article on the topic: Stress, learning and memory formation – friends or foes.

Although the stress response is complex it is generally understood, unlike the process of memory formation.

How memories are made

Memory is one of the most powerful, but least well understood, functions of the human brain. While it is not completely understood, there are several models of memory that exist, with the most well-known being the Atkinson-Shiffrin Memory Model (ASMM) or the multi-store model.6

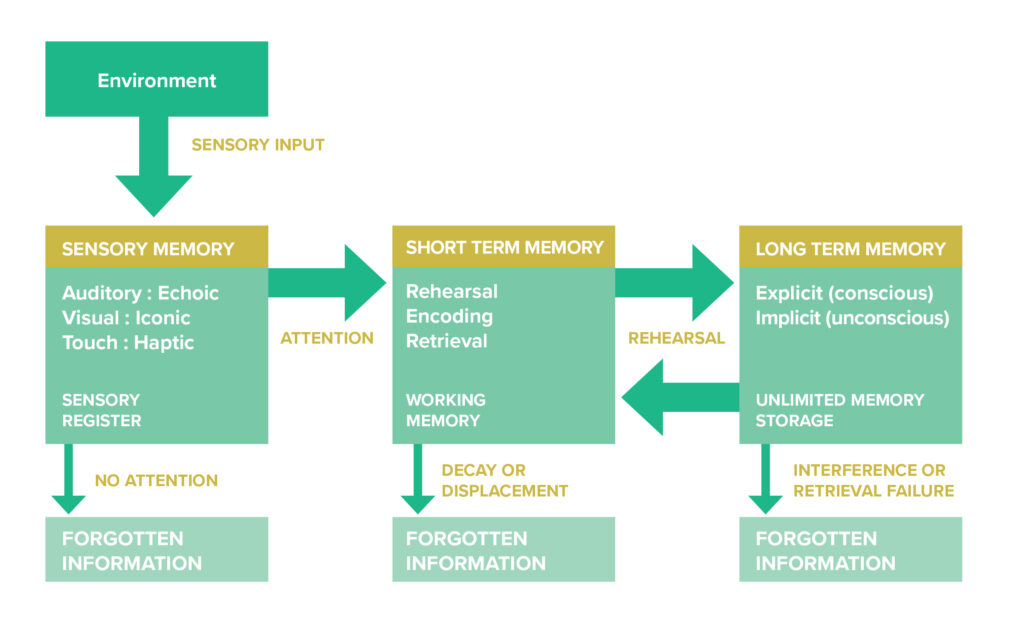

The multi-store model proposes that memory exists in three separate stages: sensory memory, short-term memory and long-term memory.6

In this model the information from the environment is first stored by sensory memory, enabling the storage and future use of such information. It is then transferred to short-term memory while being processed, before being committed to long-term memory where it can be stored for longer periods and retrieved consciously or unconsciously.7

There are three key processes in memory formation – encoding, consolidation and retrieval.

- Encoding is the process of information entering the memory – it is generally an active process as attention to the information is required for encoding

- Consolidation is the process of information being kept in the memory (storage)

- Retrieval is recalling information previously stored in the memory – it is assisted when new memories are connected to existing memories8

Stages of memory: Sensory memory

Information from the environment is first stored in sensory memory. There are three types of sensory memory:

- echoic memory retains information from auditory signals

- iconic memory retains information from visual signals

- haptic memory retains information acquired through touch.7

Each type of signal is processed in a specialised area of the neocortex and is then transformed into chemical and physical signals for processing within the body.6,9

Sensory memory retains information for 800 milliseconds to 1 second before passing the information on to the short-term memory where it undergoes the processes of encoding, rehearsing, retrieving, and responding.6,7

Stages of memory: Short-term memory

Short-term memory receives information from the sensory memory but can also access information from long-term memory. This enables reasoning and building of new conclusions from existing stored memories. Short-term memory includes the working memory, which retains and manipulates information temporarily as part of essential cognitive tasks, such as learning, reasoning, and understanding.7

Short-term memory is important for the overall processing of information. It also controls the executive system, responsible for the coordination and control of actions required to acquire new material and recovering old material in long-term storage.

It enables the brain to keep a small amount of information available for a short period of time (usually up to 30 seconds) for processing, before sending it on to long-term memory.7,10

Information stays in the short-term memory while it remains the focus of attention – a process known as rehearsing, which involves actively repeating the information within the mind.8

Diagram adapted from: Camina E, Güell F. The neuroanatomical, neurophysiological and psychological basis of memory: current models and their origins. Front. Pharmacol. 2017;8:438; Hong Z, Chen Z et al. Multi-store tracker (MUSTer): a cognitive psychology inspired approach to object tracking. In proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 2015 (pp. 749-758).

Stages of memory: Long-term memory

Long-term memory is where information is maintained for long periods, even for life.7 When a particular pattern of information or action is received repeatedly, long-term memory is activated and the pattern of information is retained. Once memorised, the pattern is maintained for a certain period of time but forgotten if not reinforced.6

There are two types of long-term memory: explicit and implicit memory. Explicit memory refers to information that is consciously and deliberately stored and recalled, while implicit memory involves unconscious or automatic memories.7

Where are memories stored in the brain?

Memories are not stored in one part of the brain – the different types of memories are stored across different, interconnected regions of the brain.11

Sensory memory is located primarily in the neocortex, while short-term memory and working memory rely primarily on the prefrontal cortex.10,11 Explicit long-term memories rely on three areas of the brain – the hippocampus, the neocortex and the amygdala. Implicit long-term memories rely on the basal ganglia and cerebellum.10

This article has provided a brief overview of the stress response and the different stages of memory and how memory is formed. But are stress and memories friends or foes? How does stress and anxiety affect memory formation and learning?

Complimentary Webinar Series

Hear global neuroscience expert in cognition and ageing, Prof. Con Stough, provide an in-depth review of bacopa & CDRI 08.

In this two-part webinar, Prof. Stough discusses:

- Outline the complexity of cognitive processes

- Examine the numerous human clinical trials for CDRI 08

- Discuss the positive outcomes of CDRI 08 on learning, memory and mild anxiety

- Describe the evidence-based clinical uses for CDRI 08

- Reveal the two key factors that underpin cognitive ageing and are improved by CDRI 08

Upon completion of the webinar, you will be able to download a participation certificate and a learning summary statement for registering CPE points.

References:

- Yaribeygi H, Panahi Y et al. The impact of stress on body function: A review. EXCLI J. 2017;16:1057-1072.

- Hannibal KE, Bishop MD. Chronic stress, cortisol dysfunction, and pain: a psychoneuroendocrine rationale for stress management in pain rehabilitation. Phys Ther. 2014;94:1816–825.

- Vogel L, Schwabe L. Learning and memory under stress: implications for the classroom. NPJ Sci Learn. 2016;1:16011.

- Girotti M et al. Prefrontal cortex executive processes affected by stress in health and disease. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;85:161-179.

- Cohen S, et al. A stage model of stress and disease. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2016;11(4):456–463.

- Hong Z, Chen Z et al. Multi-store tracker (MUSTer): a cognitive psychology inspired approach to object tracking. In proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 2015 (pp. 749-758).

- Camina E, Güell F. The neuroanatomical, neurophysiological and psychological basis of memory: current models and their origins. Front. Pharmacol. 2017;8:438.

- McBride DM, Cooper CJ. Chapter 5: Memory structures and processes. In Cognitive psychology: theory, process, and methodology 2nd ed., Sage Publications, USA; 2018. p.107

- Cascella M, Al Khalili Y. Short term memory impairment. In: Stat Pearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545136/

- Aschauer D, Rumpel S. The sensory neocortex and associative memory. In Clark RE, Martin SJ (Eds) Behavioral neuroscience of learning and memory. Springer International Publishing, Switzerland; 2018. p180.

- Queensland Brain Institute. Where are memories stored in the brain? 2018. Available from: https://qbi.uq.edu.au/brain-basics/memory/where-are-memories-stored